Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Vendan Ananda Kumararajah

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

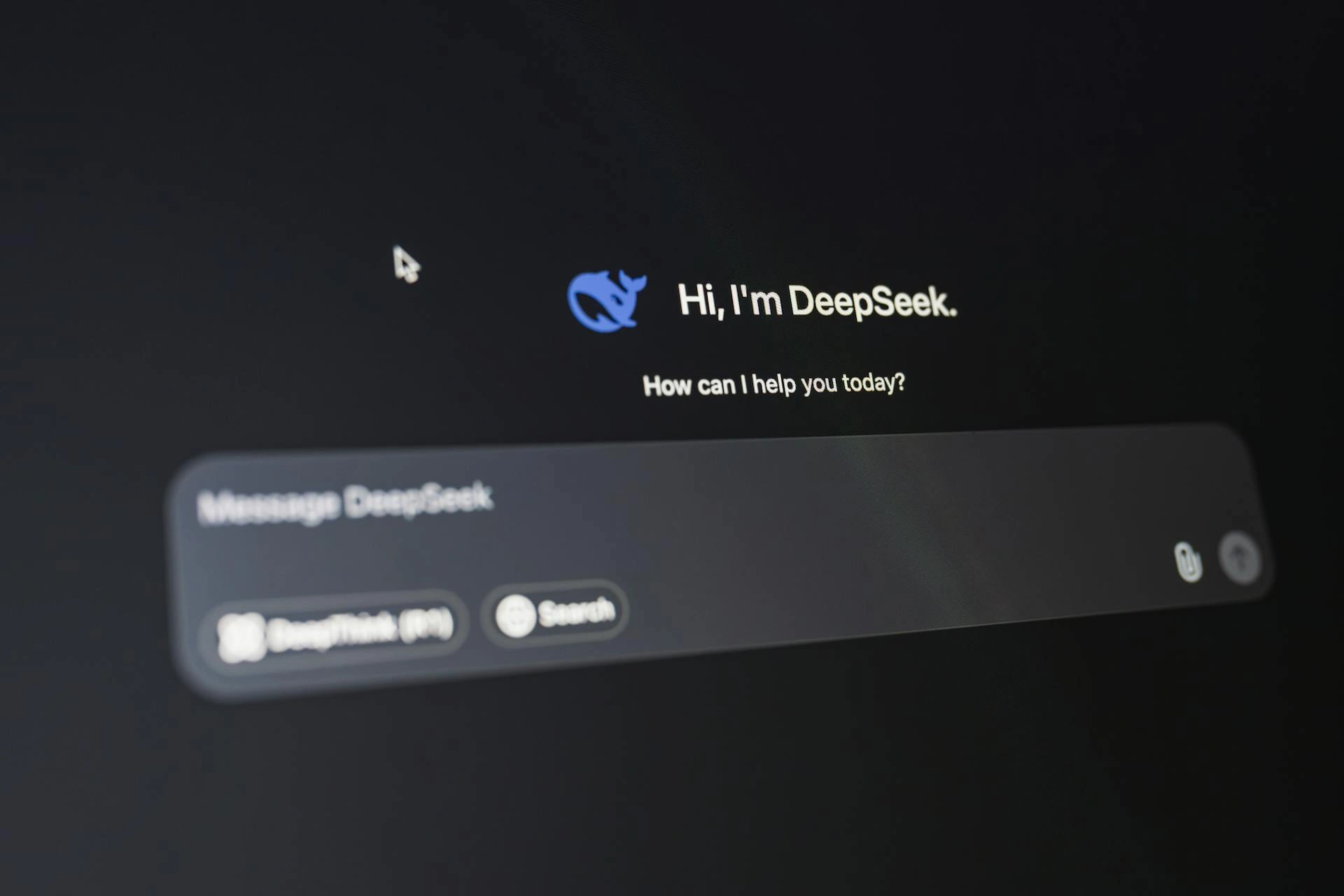

Wearables, chatbots and digital assistants now provide guidance that once came from nurses and GPs. Millions of people act on this advice when deciding whether to wait, book a GP appointment or go to A&E, and this carries real implications for risk, cost and triage. The absence of clear duties, liability and oversight has created a new advisory layer that sits outside the medical rules the system relies on, warns Vendan Kumararajah

People now ask AI systems about health in the same way they once asked doctors, nurses or pharmacists. A mother with a child who keeps coughing may type symptoms into a chatbot in the kitchen while making breakfast. A young man who worries about hair loss might ask an AI assistant during his commute. Someone who feels chest discomfort late at night might talk to a voice agent on a smart speaker because it feels easier than bothering the NHS. Wearable devices already nudge people about their sleep, their stress and their heart rate, and many of these tools speak in natural language about what to do next.

Health advice has crept into homes, offices and pockets without the need for appointments and without long waiting times. This has changed the structure of healthcare because the advisory role has shifted into tools that sit outside the rules and norms that have traditionally governed medicine.

The advice that AI provides directly steers people how to behave. A woman who has pelvic pain and is told it may settle on its own will usually wait, plan a GP visit for next week or try home remedies. Another woman with the same pain who is told it could be serious may call 111 or go to A&E that same evening. These forks in decision-making shape demand, cost and risk within the health system. Doctors and nurses train for years to understand this power. They hold licences, professional duties and liability because their advice carries real consequences. But AI agents influence the same decisions but do so without the moral, legal and institutional guardrails that surround clinical guidance.

Current regulation focuses on data privacy, transparency and recall procedures for unsafe products. These efforts matter, but they do not answer a basic question about responsibility. When a chatbot or wearable gives advice that alters behaviour around pregnancy, medication, psychiatric symptoms or care for vulnerable relatives, for example, who owns that advisory outcome? Developers place disclaimers on their products that push judgement back onto the user. The average person does not read probabilistic outputs as mere probabilities but as expert guidance that should be followed. Clinicians then meet patients whose choices have been shaped before the appointment, yet have no insight into the digital pathways that produced those choices. Regulators and courts tend to appear only after failures become visible, long after the moment where early stewardship could have prevented harm.

Good governance needs to move to the point where advice is given. At that point, clear rules should define what an AI agent may handle alone and what must trigger escalation to a human clinician. Chest pain, suicidal ideation, pregnancy complications, signs of stroke and medication misuse are not edge cases; they appear daily in primary care and emergency departments, which means any system that advises on them should face defined obligations. Certification could recognise these agents as active participants within the healthcare system rather than as neutral information tools.

Other sectors already understand advisory power. Banks cannot recommend complex financial products without suitability checks, for instance. Airlines require escalation from pilots to ground control when instruments behave unpredictably. Pharmaceutical companies must run post-marketing surveillance with real-time reporting duties. AI healthcare deserves rules of similar sophistication.

AI models change all the time. Updates alter their tone, their confidence levels and their triage suggestions. These changes look subtle at first and usually become visible only when patterns emerge across large populations. Approval regimes that sign off a product once and then step away cannot manage technology that rewrites itself every few weeks.

Continuous monitoring, longitudinal audits and performance tracking would provide a realistic foundation for safety. Without such structures, society ends up running a vast uncontrolled experiment on millions of people who have no way to understand the risks, the incentives or the absence of governance around these advisory conversations.

Europe already has institutions that understand advice, risk and public interest. Its medical device framework, its pharmaceutical rules and its financial supervisory systems already deal with high-stakes guidance and cross-border enforcement. The task ahead is not to invent an entirely new philosophy of responsible AI but to adapt existing machinery to a new actor that sits in a grey zone between clinical care and consumer technology. Influence needs liability, function needs certification and patients need protections at the point where behaviour is shaped.

Without it, healthcare across Europe and beyond will develop a hidden advisory layer with no clear owner, no monitoring and no accountability. That would erode public trust in medicine and technology alike, and it would place a burden on patients that they never agreed to shoulder.

Vendan Ananda Kumararajah is an internationally recognised transformation architect and systems thinker. The originator of the A3 Model—a new-order cybernetic framework uniting ethics, distortion awareness, and agency in AI and governance—he bridges ancient Tamil philosophy with contemporary systems science. A Member of the Chartered Management Institute and author of Navigating Complexity and System Challenges: Foundations for the A3 Model (2025), Vendan is redefining how intelligence, governance, and ethics interconnect in an age of autonomous technologies.

READ MORE: ‘Robots can’t care — and believing they can will break our health system‘. Artificial intelligence is being hailed as the next frontier in healthcare but as broadcaster and disability rights advocate Matthew Kayne writes, empathy cannot be automated. Real care exists in human presence, in the moments of understanding that only people can offer.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Karola G/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation -

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting -

The fight for Greenland begins…again

The fight for Greenland begins…again -

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped -

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation -

Europe’s space ambitions are stuck in political orbit

Europe’s space ambitions are stuck in political orbit -

New Year, same question: will I be able to leave the house today?

New Year, same question: will I be able to leave the house today? -

A New Year wake-up call on water safety

A New Year wake-up call on water safety -

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it -

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns